Here’s an extract from my latest book, Return from The End Of The Line, which I published just before Christmas 2023. If this chapter whets your appetite, then hurry along to my bookstore as the January sale continues until the 31st of the month. Here’s a link to get you there quickly.

Many events since the early 19th century have shaped today’s rich and varied railway network. I hope this summary will give you some background on the railway’s development and help you understand more about today’s Train Operating Companies (TOCs). I’ve gone into more detail in each chapter. My journey encompasses London’s commuter rail network and destinations that fit my definition of an end-of-the-line. However, I recognise the eleven TOCs whose rail networks I have travelled across stretch well beyond my reach.

For the avoidance of doubt, the eleven London commuter TOCs I have travelled with are c2c, Chilterns Railway, Great Northern Railway, Great Western Railway, Greater Anglia, London Northwestern Railway, South Western Railway, Southeastern, Southeastern High Speed, Southern Rail and Thameslink. Rail enthusiasts will know that the same parent company owns some of these companies, but they chose to operate under a historical name in homage to the original rail company. I’ll cover the details throughout this book. Finally, the current franchise/contract operating model is a moving beast, so treat this summary as a moment in time.

The Railway Explosion

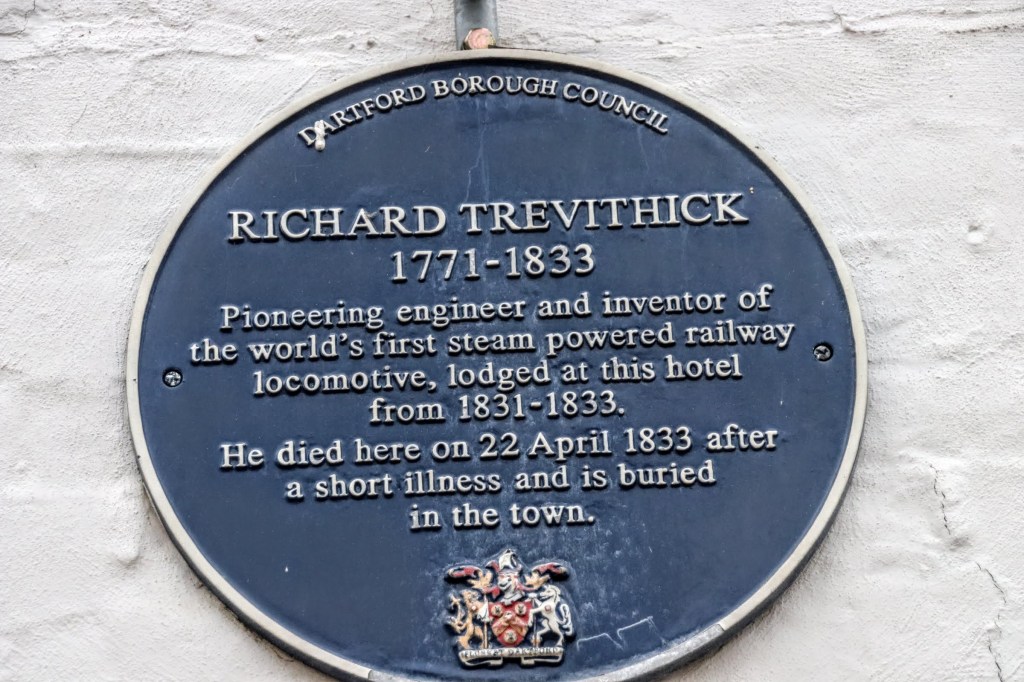

I think it’s fair to say the need to move minerals was the industrial spark that led to steam power and, ultimately, the creation of steam trains to carry and move goods. Coal was the predominant mineral from the 16th century when hand carts or horse-drawn carts were used. Of course, other mining industries across the UK were part of this revolution too. The first recorded steam locomotive was built by Richard Trevithick and used to haul iron from Merthyr Tydfil to Abercynon, Wales, in 1804. You’ll find a mention of Richard Trevithick in my visit to Dartford.

On the 26th of December 1825, the renowned ‘Father of Railways’, George Stephenson, opened the first steam-powered passenger railway between Stockton & Darlington. His son, Robert Stephenson, then designed and built the renowned ‘Rocket’ in 1829 to demonstrate that improved locomotives would be more efficient than stationary steam engines. London’s first steam railway ran between Tooley Street and Greenwich, built between 1836 and 1838 by the London & Greenwich Railway (L&GR). Parts of the preserved elevated arches can still be seen today by Deptford station.

In the 1840s, the railway boom took hold with over 250 Acts of Parliament approving new railway companies against an otherwise blank canvas. Investors saw an opportunity to make a quick win, which saw the price of investment increase, further attracting more investment. Inevitably, the boom was unsustainable, with many companies not being formed, failing or even being taken over by other companies. Some fraudulent enterprises resulted, most notably that of George Hudson. You can read more about him in the Great Northern chapter. By the mid-19th century, investment was more cautious, and the boom slowed. Nevertheless, railway companies came and went, and by the early 1920s, there had been almost three hundred individual companies operating passenger or goods services across Great Britain.

With so many companies operating independently, larger, more profitable companies started to consolidate their geographical reach, absorbing smaller rail companies that they may already have been supporting financially.

One of the obstacles that challenged the amalgamation of companies, and subsequently the ability to move rolling stock between companies, was the track gauge size. This wasn’t a consideration during the early boom when companies determined their own track gauge. Two gauges dominated. Isambard Kingdom Brunel, who was contracted to design and build parts of the Great Western Railway, adopted a broad gauge of 7’ ¼” (seven feet and a quarter inch, 2140mm) as this provided greater stability for engines to travel faster. Other companies adopted a track gauge of 4’ 8 ½” (four feet, eight and a half inch, 1435mm) which became known as the standard gauge. Following an Act of Parliament in 1846, all new railway companies were mandated to adopt the standard gauge. However, it wasn’t until 1892 that the Great Western Railway converted all their tracks and trains to standard gauge.

The War Years

At the outbreak of the First World War in 1914, most railways were taken into government control and run by their Railway Executive Committee. As staff joined the armed forces, it was difficult to maintain and build equipment, and remained so after the war, with companies failing to recover financially through loss of revenue. However, the government’s control of the railways during the war revealed some advantages to running the railways with fewer companies and calls for its nationalisation resurfaced, having first been mooted by William Gladstone in the 1830s. It failed to curry favour again. However, the railway companies agreed to a compromise with the government, grouping the hundred or so remaining railway companies into four new companies – known as The Big Four.

The Big Four railway companies were Great Western (GWR), London, Midland and Scottish Railway (LMS), London and North Eastern Railway (LNER), and Southern Railway (SR).

The period between the wars brought another challenge to the railway’s monopoly on how goods were transported around the country. Following the First World War, freight became cheaper to transport by road because of a surplus of vans and lorries and the subsidised construction of road improvements. The railway companies could not compete financially as road haulage companies had fewer restrictions on how they charged for carrying goods and were able to introduce door-to-door deliveries. The rail companies saw this as an unfair advantage and raised many concerns with the government about the uncontrolled growth of road haulage and the need for greater safety on hauliers. This led to implementing the Salter Report recommendations in 1933, seeing an easement to some of the railways’ restrictions. Furthermore, the report was the instigator in introducing hauliers’ safety regulations and licensing and ultimately introducing the vehicle excise duty for all motor vehicles, an unpopular decision.

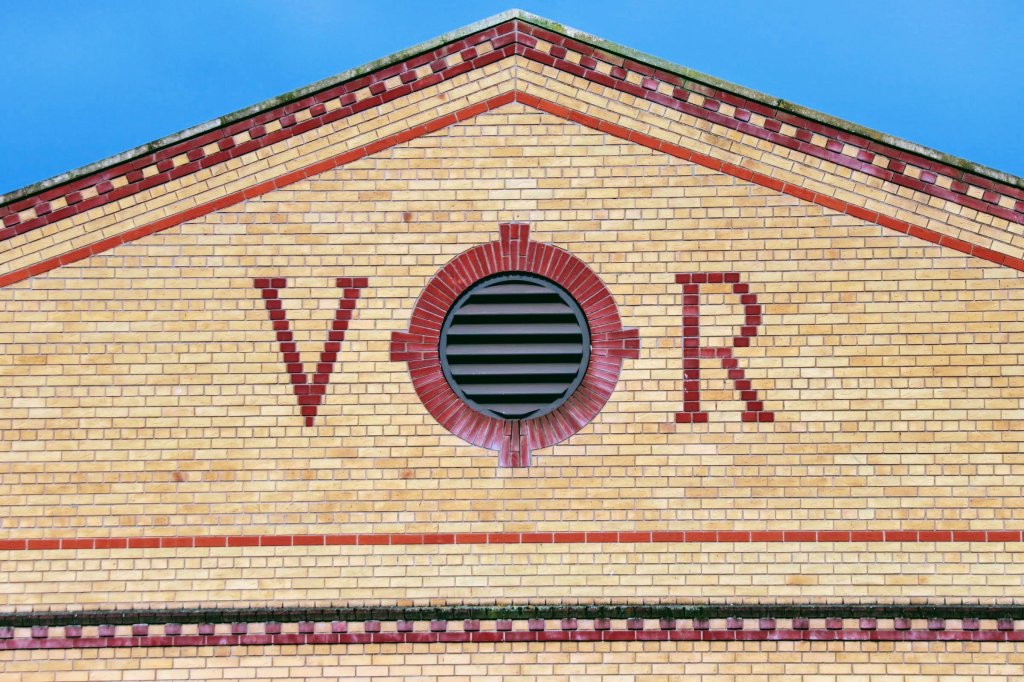

During the 1920s and 1930s, the railway companies’ efforts were directed at rebuilding their railways, improving engine design and rolling stock. Electrification of the railways began with Southern Rail’s main-line service. However, the growth in popularity of the car resulted in passenger numbers declining and the closure of underused branch lines.

The Second World War saw the Big Four manage their network as one company, and ironically, the period brought about unprecedented growth in rail transport. There was little profit, as the transport growth was all related to supporting the war effort by carrying troops and freight towards the south coast. The infrastructure in London and Coventry suffered heavy bomb damage, too.

It didn’t take long after the Second World War to nationalise the railway network. The financial strains of two world wars and a change in passenger and freight traffic brought about the inevitable as the railways remained unprofitable. Nationalisation of public services was also a mandate of the post-war Labour Government, and the Transport Act 1947 created British Railways on the 1st of January 1948. Closure of some unprofitable lines began immediately. The railway’s continued decline led to the publication of a ‘Modernisation Plan’ in 1955, which aimed to reduce the financial debt. The Plan was soon followed by a government White Paper in 1956 endorsing electrification, replacing all steam locomotives with diesel engines, and the continued closure of lines and stations.

British Rail

Changes introduced by the Transport Act 1962 saw British Railways management change from a Railways Executive to the British Railways Board in January 1963. The Board’s first chairman, Dr Richard Beeching, published his ‘The Reshaping of British Railways’ report in March 1963. His report, known as the ‘Beeching Cuts’, advocated the closure of a third of all passenger services and four thousand station closures. Successive Labour and Conservative governments supported the closure programme through to 1970.

The well-known double-arrow logo was introduced in 1965, which has since become synonymous with a railway station, and its introduction saw British Railways truncate its name to British Rail. There were many changes from the 1970s through to the early 1990s.

Here are a few:

- Local communities managed their area’s networks through Passenger Transport Executives.

- Passenger transport was sectorised by function with the creation of Inter City, Regional Railways (there were seven) and Network SouthEast for London commuter services.

- A new ticketing system called the Accountancy and Passenger Ticket Issuing System (APTIS) produces today’s tickets. In London, these have since been replaced with the Oyster Card.

Privatisation

Margaret Thatcher’s Conservative Government, elected in 1979, began dismantling Britain’s state-owned businesses in the belief that private competition would deliver improvements through investment and competition. Privatising British Rail began with selling some related services in the 1980s. They included Sealink (ferries), British Transport Hotels, Travellers Fare (catering) and British Rail Engineering Limited (train building).

It was John Major, Thatcher’s successor, who implemented the privatisation of the rail network on the back of the European Directive 91/440, requiring all EU member states to separate “the management of railway operation and infrastructure from the provision of railway transport services…”, the idea being that the track operator would charge the train operator a transparent fee to run its trains over the network. Anyone else could also run trains under the same conditions. The Railways Act 1993 provided the requisite legislation, resulting in British Rail being sold off by 1997.

Rail passenger services were sold off to twenty-five Train Operating Companies (TOCs), freight services were sold off to two Freight Operating Companies (FOCs), and Railtrack took ownership of the infrastructure. The Hatfield rail crash in 2000 was a defining moment for Railtrack as it could not recover from the financial implications of the accident. Consequently, Network Rail, an arms-length public body of the Department of Transport, took over ownership of the infrastructure in 2002.

Franchise arrangements were awarded to TOCs who agreed to deliver a specific passenger service against set performance targets for a defined period and relied on the TOCs paying the government a fee based on anticipated passenger revenue. This arrangement remained unchanged for twenty-five years. However, the Covid pandemic significantly impacted the rail passenger industry, which led to the government subsidising TOCs so they could continue to operate. Consequently, a new operating framework was published in 2021, introducing Passenger Service Contracts (PSCs) instead of franchise agreements. The contracts are awarded directly to TOCs by the Department of Transport in England. These arrangements are operated under a new organisation called Great British Railways, ensuring passenger interests are at the heart of planning and delivery. Separate arrangements exist in the devolved nations.

The franchise model hasn’t been a success as several TOCs have failed, and rail operations had to be transferred to the Operator of Last Resort on behalf of the Department of Transport. Southeastern, across London, is one of them.

The following provides a high-level ownership view of London’s Commuter Train Operating Companies.

| TOC | Franchise | Owner | Miles (Km) | Stations Called at | Stations Operated |

| c2c | Essex Thameside | Trenitalia | 125 | 28 | 25 |

| Chiltern Railways | Chiltern | Arriva | 336 | 66 | 32 |

| Great Northern | Thameslink, Southern & Greater Northern | Go-Ahead GroupKeolis | 1300 | 339 | 238 |

| Great Western Railway | Great Western | FirstGroup | 1323 | 270 | 198 |

| Greater Anglia | East Anglia | Transport UK GroupMitsui | Circ. 650 | 150 | 134 |

| London Northwestern Railway (West Midlands Train) | West Midlands | Transport UK GroupEast Japan Railway CompanyMitsui | 867 | 178 | 146 |

| South Western Railway | South Western | FirstGroupMTR Corporation | 3629 | 384 | 384 |

| Southeastern | South Eastern | DfT OLR Holdings | 870 | 180 | 164 |

| Southeastern High Speed | South Eastern | DfT OLR Holdings | See Southeastern | ||

| Southern Rail | Thameslink, Southern & Greater Northern | Go-Ahead GroupKeolis | See Great Northern | ||

| Thameslink | Thameslink, Southern & Greater Northern | Go-Ahead GroupKeolis | See Great Northern | ||

Leave a comment